More than just a pretty picture.....

Oo oo ah ah!!!

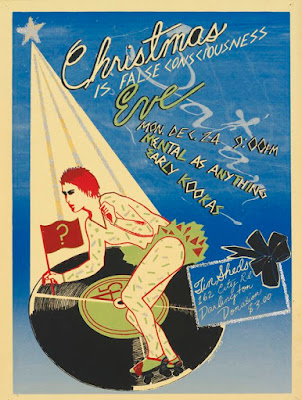

During 2019 this author acquired a poster advertising a 1979 fund-raising dance held at the Tin Sheds, University of Sydney, and featuring local Australian bands Early Kookas and The Gents. The main subject of the poster was the tilted, upper body section of what appeared to be a smiling, bow-tie wearing, male game show host or waiter but was, according to one of the artist's involved, a 'male figure from an English book [on] ballroom dancing [who] was one of the presenters' (Mackay 2019). The man sported a dinner jacket artificially emblazoned with Australian kookaburras and held in both hands what appeared to be a role of paper. Aged about 40, he was staring intently out at the viewer with a decidedly warm, welcoming and friendly demeanor. Behind him a stunning array of flowers in fluorescent pink and yellow set the scene. The bright green kookaburras on his jacket were a similar standout. In the lower left-hand corner was the distinctive logo of the Earthworks Poster Collective.

|

| Logo on Oo Ah Dance poster. |

Earthworks operated out of the ramshackle Tin Sheds complex at the University of Sydney between 1972 and 1980 (Kenyon 1995, Brown 2006). The facility had been set up in late 1968 / early 1969 by a group led by Donald Brook, Marr Grounds, and sculptor, painter and print maker Bert Flugelman. It was envisioned as a full time art workshop, democratically open to all comers. The site had previously been used by the CSIRO and artist and fellow University of Sydney lecturer Lloyd Rees. The facility went on to be managed by Guy Warren and Joan Grounds through to 1979. Flugelman was one of the early drivers in transforming the Tin Sheds into an engaging art workshop and exhibition and performance space, encouraging all manner of artistic expression and use by students and members of the local community, amidst his own experimental endeavours in the area of sculpture, painting and multimedia such as the Optronic Kinetics project. Flugelman's notable 'Burning Euphonium (Homage to Magritte)' in the backyard of the Tin Sheds was a well known example of the innovation and experimental spirit at work within the facility. Flugelman later worked at the University of Wollongong, south of Sydney, all the while continuing to produce distinctive and world renown artworks, especially works of sculpture.

At the Tin Sheds complex Flugelman brought together engineering students, artists and architects to work on various projects, such was the openness and eclectic nature of his stewardship. The fact that it was both part of, and separate from, the University of Sydney, enabled this eclecticism to evolve in regards to usage and support. The nature of the support - both given and not given to the Tin Sheds - is outlined in an article written by one of its most active participants - Chips Mackinolty - in 1977 at the height of activity there. Therein he noted that the Tin Sheds as an entity was .....free of the worst excesses of the 'art world' [and] .... something rather like a sheltered workshop' (Mackinolty 1977).

Poster printing had commenced at the Tin Sheds - in the bottom shed according to one account - at some point during the early 1970s (Allam 2008). By 1972 Colin Little was the driving force in print production. The origin of Earthworks dates to that year with the creation of a poster by Axel Sutinen and Little for an exhibition held at Martin Sharp's Yellow House (Organ 2015). The Yellow House was an artists' collective located on the opposite, eastern side of Sydney at Potts Point, within a three storey Victorian terrace. It existed from the middle of 1970 through to early 1973 and operated as an innovative multimedia space contemporaneously with the Tin Sheds. Sharp saw it as a continuation of the ideal of Vincent Van Gogh in his Yellow House at Arles, and of The Pheasantry in London which the Australian artist had occupied between 1966-68, alongside comrades and compatriots such as Eric Clapton, Germaine Greer, Robert Whitaker and Phillipe Mora.

Participation in the Earthworks Poster Collective peaked between 1975 and 1979, with round-the-clock poster production and a number of artists residing at the facility. Subjects covered by Earthworks' student artists and community members varied, ranging from political commentary spurred on by the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975, through critiques of contemporary social movements, promotion of community events including fundraisers, concerts and exhibitions, and celebrations of anniversaries such as International Women's Day and May Day.

One of the many posters produced by the Earthworks Poster Collective was 1979's The OO OO AH AH OO AH AH by Jan Mackay and Chips Mackinolty (referred to hereafter as Oo Ah Dance). It was so-called due to the black text announcing the event which ran across the upper right half of the image, against the busy pink, yellow and white background. The lower section comprised a large, triangular block of yellow. Like any good street poster, within it were specific details of the dance being advertised, including when, where, why and how much to get in. Utilizing bright, oil-based, fluorescent and flat inks in pink, pale green and yellow, alongside grey and black for definition and text, the work vibrated with an intensity reminiscent of 1960s psychedelic rock concert posters, similar to those coming out of San Francisco and London and announcing concerts by bands such as Jefferson Airplane, the Yardbirds, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and The Who.

|

| Fillmore poster, 1967. |

Distinguished by their swirling fonts and bright colours - often the result of the artist experiencing the mind altering effects of hallucinogenic drugs such as LSD (acid) - these concert posters set a new benchmark in graphic design and the promotion of pop culture events. Printing processes such as machine offset photolithography were preferred as they allowed for the production of literally thousands of posters with minimal degradation in the quality of the print. The largely manual silkscreen process, like that of the once popular stone lithography, was a more direct and cheaper method by which artists could replicate their work, though print runs were limited to the hundreds, rather than thousands, and images were subject to degradation as the drawing on stone or via silkscreen wore away with each imprint. Offset photolithography required large, mechanical printing presses and experienced operators; silkscreen printing merely required wood-framed screens, benches and racks. In all instances the artistry and technical expertise of those involved was paramount.

Oo Ah Dance is undoubtedly one of the most vivid of the approximately 270 known Earthworks posters. Its production came towards the end of the Collective's peak and is reflective of the skills the various practitioners had attained by that stage. The use of the silkscreen printing technique enhanced the poster's impact, providing it with relatively thick layers of solvent-based paint and large blocks of solid, texture-free colour. Its 51 by 76 centimetre dimensions also added to this, though most Earthworks posters were of a similarly large size. The aforementioned Sixties psychedelic rock music posters coming out of San Francisco were approximately half the size at 36 by 50 centimetres.

The Earthworks Poster Collective became internationally renown for its use of the silk screening process during this period, producing posters full of colour, innovative graphic design, humour and contemporary commentary. Members such as Chips Mackinolty, Leonie Lane, Marie McMahon and Michael Callaghan developed expertise in its application, whilst the latter went on to pursue a career as master printer with Redback Graphix during the 1980s (Zagala 2008). His death in 2012 was related, in part, to the toxicity of the chemicals utilised during his many years silkscreen printing at the Tin Sheds, as was the earlier passing of Colin Little in 1979. Whilst poster production was the main work undertaken by the Earthworks Poster Collective, other printing jobs included flyers, t-shirts, textiles and book covers. A video from 1979 shows a group of people printing a series of book covers there.

Silkscreen printing at the Tin Sheds, 1979. Featuring Mickey Allan, Pam Brown and Ray Young. It is possible that Ray Young is the Ray referred to in the Oo Ah Dance poster. Source: YouTube.

The video reveals the relatively crowded space in the bottom shed and some of the elements of the printing process, including the application of inks to the prepared screens. Each colour was applied separately by hand, giving rise to an individuality in the print not seen with machine production.

In addition to printing by artists associated with the Collective, members of the local community and fringe dwellers such as the Melbourne-born Toby Zoates - who was not a student at the time, or officially recognised as part of the Collective - made use of the facility. Zoates worked at the Tin Sheds between 1977 and 1980, wherein he received assistance and training in printing street posters from Mackinolty and Callaghan. He is known to have printed at least 17 different posters there, utilising materials such as unwanted cans of fluorescent paint and the blank sides of sheets of computer printout (Organ 2019). Groups such as the substantially female Lucifoil Poster Collective (1980-83) later made use of the Tin Sheds facilities as individual skills increased, the support base expanded and diversified, and mainstays such as Mackinolty, Mackay and Callaghan move on.

In June 2019 Chips Mackinolty remembered the following in regards to the Oo Ah Dance poster and the circumstances surrounding its creation:

It was one of many posters we produced in those days for [Tin] Sheds dances, producing good money for bands and profits ploughed back into the Sheds generally, or the upkeep of Earthworks. It was put together by Jan Mackay and I as one of those almost "routine" things, though from distant memory one of the beneficiaries was Doris, a cat, to pay for a vet bill or some such. For me it was my first foray into fabric design, i.e. the repeat pattern on the jacket. All the lettering [was] by Jan, and the repeat frangipani design in the background.

Chips Mackinolty screen printing at the Tin Sheds circa 1977 (Kenyon 1995).

The usual run for these posters was 300. There are copies in a few public collections. A good night [was] had by all! And yes it was at the end of my time at the Sheds - [I] left in January 1980. By that stage Earthworks had decided to disband, though posters were made under that name until about February or so 1980. Ray [Young] left for Nguiu on Bathurst Island not so long after this was shot - and yes it was his cat! One inaccuracy: Earthworks never got Visual Arts Board funding for the Collective, though in late 1979 we did apply and were knocked back. [This was] one of the reasons for not continuing the effort. As I have written elsewhere, we were also tired and a bit sick of poverty. (Chips Mackinolty, email to the author, 19 June 2019).

At the 50 Not Out exhibition of his works at the Damien Minton Salon, Sydney, on 1 September 2019, Chips informed the author in regards to the Oo Ah Dance poster:

This was a time when we started to use fluorescent paints. We would also mix the fluorescent paint in with other paints to create an effect. Michael Callaghan went on to make a lot of use of this in his work with Redback Graphix.

|

| Oo Ah Dance poster 1979. |

Jan Mackay also provided some comments in regard to the origins of the poster and its production:

The repeat pattern on his suit makes reference to the Early Kookas band and the wild floral patterned ground is anybody’s guess, but I will say that I (and others) were interested in patterning and fabric printing. I, along with Marie McMahon, had learned to screen print at the National Art School, East Sydney Technical College, Darlinghurst, when we were students there, before becoming involved with Earthworks and the Tin Sheds. Chips and I shared the design and printing on this poster. Even if one person was designing a poster and printing it, one would always need a racker to put the posters in the drying rack (Jan Mackay, email to the author, 1 July 2019).

The copy of Oo Ah Dance acquired by the writer was not your typical, 40 year old, sun-faded, photo-lithographic gig poster printed on thin paper or newsprint and pulled out of the centre of a magazine or newspaper. Rather, it was the graphic equivalent of an oil painting on canvas, still dazzling despite its age, though a bit rough around the edges. The individual artistry of both Jan Mackay and Chips Mackinolty is evident in the quality of the graphic design and execution of the hand-pulled, silkscreen printing process. The author was initially attracted to this poster by its vibrant colours and placement of the various design elements, rather than any specific content or context, of which nothing was known. It had first been noticed in a 2017 Lawson's auction and at the Damien Minton Tin Shed Posters exhibition and sale the following year (Minton 2018). In both instances extremely fine examples of the poster were offered for sale and sold accordingly at high prices. The copy obtained showed evidence of its age and use. It was mounted on board and lacked archival framing or a protective covering. The accumulated signs of age included scuff marks on the surface, dirt, rust stains, watermarks, a missing corner, and small tears and silverfish attack around the edges. Some contemporaneous printing artifacts may also have been present among these imperfections. Like most pop culture posters from the 1960s and 1970s, it had been loved and displayed in public by previous owners, not hidden away. As an archivist, the writer was acutely aware of the commonality of such treatment, and of the fragile nature of these largely ephemeral artworks. Their fate was generally to be taped, tacked, glued or otherwise stuck up on walls and ultimately binned if not rescued. Fortunately the colours were still vibrant and it bore its scars with dignity. The poster was therefore embraced in all its brightness, energy, beauty and historic significance as a true work of art, reflecting the fact that "This is the real deal" and not a vapid reprint with no depth, texture or individuality.

Oo Ah Dance was acquired by this author from Wendy Murray, a fellow poster enthusiast and practicing artist and print maker famous for her Sydney street posters and as the artist formerly known as Mini Graf. The story of her initial acquisition is an interesting one. Early one morning sometime around 2006 the poster was spotted by sculptor Will Coles for sale in The Cat Protection Society of New South Wales op-shop on Enmore Road, Sydney. Coles suggested to his friend that she 'pop in and get it', which she immediately did.

The artist's respect for the work was obvious. Upon acquisition by the present author, a process therefore commenced of investigating the poster's origins and what it was as a thing, recording any findings in the current blog. Ownership ignited a keenness to discover more about the work, in and of itself, and outside its role in igniting memories of a time when going to gigs was a regular occurrence amidst a late 1970s renaissance in Australian popular music and the east coast pub rock scene. This path began when, shortly after receiving the poster, research revealed an account by Victorian researcher Petra Mosman of an intervention at the opening of the Girls at the Tin Sheds exhibitions at the University of Sydney early in 2015. The present author had visited the exhibitions at the time, but was not in attendance at either of the two opening events. At that point came a realisation of the significance of Oo Ah Dance beyond its age and obvious aesthetic qualities.

The Girls at the Tin Sheds - intervention

In 2015 the Melbourne-based researcher Petra Mosman published an account of an incident concerning the Oo Ah Dance poster, or rather, her presence at an event in which its relevance was proclaimed in no uncertain terms by one of the parties involved in its creation. The following extract from Mosman's 2018 PhD thesis on aspects of Second Wave Feminism in Australia refers to that encounter and replicates much of what was presented in the earlier report:

Girls at the Tin Sheds Gallery Opening, Verge Gallery, Sydney, 7 March 2015.

I was in Sydney for the exhibition opening of Girls at the Tin Sheds (Duplicated) and at the time I had no intention of writing about the exhibition. The opening was held at Verge Gallery, the day before International Women’s Day. It was a formal opening with good catering and waiting staff. Well-known Sydney figures, Tin Sheds artists and activists, younger contemporary artists, curators, academics and Sydney university staff attended the exhibition. Well-known feminist writer and femocrat, Anne Summers, spoke at the opening.

After the formal speeches concluded, a woman hijacked the microphone. This was an incredibly rebellious act at a formal opening. The interloper was Annie Bickford. She was part of Sydney Women’s Liberation. She was not a visual artist and did not make prints, but she sang at Tin Sheds dances in a band called the ‘Early Kookas’; she is also an archaeologist and museologist. The curator of Girls at the Tin Sheds: Duplicated, Louise Mayhew braced herself, expecting criticism. Bickford drew attention to a particular poster from the Tin Sheds [not included in the exhibitions], The Oo Oo Ah Ah Oo Ah Ah Dance poster, created by Jan Mackay and Chips Mackinolty, both members of Earthworks collective. The Earthworks collective are mostly known for printing explicitly political posters, but this one was created to advertise a dance at the Tin Sheds, a dance that featured Bickford’s band. According to Bickford, for people who were part of the Tin Sheds crowd in the late 1970s The Oo Oo Ah Ah Oo Ah Ah Dance poster had a specific meaning. The ‘Oo oo ah ah oo ah ah’ which is written across it, refers to a song, ‘Why Do Fools Fall In Love’, which was originally recorded by an American band Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers in 1956.

It was one of the many songs that Bickford’s band sung in the late 1970s. [At the exhibition opening] she dramatically sang a section of the song, then explained that the band’s name refers to an Australian made stove, the Early Kooka, which features a kookaburra.

|

| Metters Early Kooka stove door. |

Although it is based on an American song, in an Australian context the ‘oo oo ah ah’ is reminiscent of a kookaburra’s bird call. These connections are referenced in the poster, as a series of kookaburras are printed across the man’s jacket. The other band playing at the dance was called ‘The Gents’, hence the depiction of a man in a suit. Furthermore, there is a curious little note on the poster. It says that the performance was a fundraiser 'For Doris and Ray'. Doris is a cat, and Ray is the cat’s owner. It is impossible to tell from the poster’s design that Doris is a cat needing to be de-sexed, hence the joke in the corner of the poster, that the event is being ‘Assisted by the vet not the Visual Arts Board’. According to Bickford, the Visual Arts Board had recently stopped providing funding. This sort of humour was part of the Tin Sheds’ aesthetic and politics, and many other posters have similar details that are impossible to read in this manner without extensive explanation from the poster maker or from people involved with the Tin Sheds. None of the poster exhibitions discussed in this [thesis] chapter provided this sort of detail for the posters they displayed. After Bickford finished telling the story of the poster and singing the song, she asked how would anyone be expected to know the context and understand such posters without narration? Rather than criticize the curators, she addressed her comments to friends from the Tin Sheds in the room, and there were many in attendance, stating that people involved in [the] Tin Sheds must work with institutions and young curators, who are my ‘peers’ to an extent, to improve documentation. She then dropped the microphone and re-joined the crowd. This disruption to the formal gallery proceeding was unusual, and reflects on the interpretation and ownership of the posters. First, the Tin Sheds was a political and aesthetic experiment and it was often an anti-authoritarian, anti-hierarchical and a DIY [do-it-yourself] art space. Bickford’s intervention gave a sense of the spaces that these posters would have inhabited, which is not legible in the exhibitions. Verge is built on the site where the Tin Sheds once stood, where rowdy, very different exhibition openings would have been held. Gallery openings would not have included university administration and formal catering. Both the formal opening at Verge Gallery, which is a beautiful glass walled white cube, and the arrangement of the posters emphasised change. Here, the university perhaps claims a heritage that it did not fully support, which perhaps represents the de‐politicisation of activist histories and contemporary practices based on those histories. Bickford’s intervention illustrated how the context of the posters had changed in this respect. Secondly, Bickford was commenting on the exhibition, on collection practice and on the relevant communities’ involvement in the process. All the exhibitions discussed in this [thesis] chapter purposefully reinterpret the posters, and none include the kind of details Bickford described when telling this story. From the exhibition catalogues, it seems likely that the curators of each exhibition knew some poster stories and could have narrated some of them in detail; however, this was not the intention of any of the exhibitions discussed here. Even if people who created the posters or knew them well provided such details, it seems unlikely that they would have been presented to audiences in an art gallery. Clearly, the curators of all four exhibitions had different understandings of their purpose in relation to the exhibitions from those described by Bickford (Mosman 2018).

--------------------

Chips Mackinolty and Jan Mackay, 50 Not Out exhibition, Damien Minton Salon, 1 September 2019.

The Oo Ah Dance poster is revealed by Bickford and Mosman to be more than simply a pretty picture, an artwork to be exhibited, or a poster produced by the Earthworks Poster Collective as purely an artistic exercise. It is a cultural artefact; the product of a unique, collaborative environment involving artists and local community. In this instance - and likely across the board in regards to the Collective's operation - it is obvious that Jan Mackay and Chips Mackinolty worked closely with Bickford and her colleagues in order to reflect elements of their own artistic endeavours, whilst also adding humour into the work. Furthermore, through Mosman's accounts the poster's relationship to the feminist movement is hinted at; the meaning of various elements are revealed; and the way in which gallery and exhibition audiences, and even individual collectors, can and should read the work is expanded upon. The lesson to be learnt is that each and every Earthworks poster, just like any individual work of art, is a story in and of itself - a story concerning the artist, or artists, involved; a story centred around, and revelatory of, the content; and a story of the context in regards to the work's origins, the creative process involved in its production, and the poster's subsequent utilisation as advertisement, artwork and ultimately historical artefact.

|

| Oo Ah Dance poster detail. |

The two artists involved in Oo Ah Dance had a long and active association with the Earthworks collective. Chips Mackinolty was a resident and one of the main screen printers at the Tin Sheds, and as such he is associated with many of the posters produced there during the 1970s, both as artist and in collaboration with others as the silkscreen printer. Earthworks was primarily an anonymous collective, with none of the works signed. It is therefore difficult to ascertain attribution with certainty, though the role of Mackay and Mackinolty in the production of the Oo Ah Dance poster is not disputed. In that instance they applied a typical mix of reproduced photo-lithographic elements - the man, the kookaburras - with original art applied behind, and on top of, the artificial elements during the silk-screening process. This is similar to the collage process which had been developed by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Hannah Hoch and Kurt Schwitters during the early 1900s and refined in the 1950s and 1960s in association with the development of Pop Art by exponents such as Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol and Australia's Martin Sharp. The final product is inexplicable, anonymous and ephemeral, though in the end not so far removed from that oil painting on canvas which has long been the mainstay of traditional gallery and museum collections and exhibitions. Though on the surface a simple composition, Oo Ah Dance comprises a number of elements which reveal the art historical perspective of both Mackay and Mackinolty as graphic designers and print makers. It was both a product of that perspective, and of the times.

Grabbing one's attention

|

| Lord Kitchiner, 1914. |

|

| Earthworks, 1977. |

The Tale of Doris the Cat

As noted above, one of the reasons behind the creation of the Oo Ah Dance poster was as a fundraiser for Doris the cat. According to a recent email from Jan Mackay, the story goes as follows:

..... Doris, the cat in question, was residing at the Sheds. I don’t have any memory of her belonging to Ray, however prior to the benefit dance for which the poster was made she gave birth to kittens in early October and had a few birthing problems, requiring her to be taken to the Sydney University vet one night. So we needed to cover the vet bill. I ended up taking the 6 week mark they were distributed to; friends..... I can’t remember who, and I became her owner / carer 'til she died around 1989. Ray Young was part of Earthworks and about to head off to work as arts advisor and manager at Tiwi Designs, Bathurst Island, Northern Territory. So from memory the benefit dance was also for Ray to give him some assistance too. (Jan Mackay email to author 24 June 2019).

The discovery in 2006 of a copy of the poster for sale in the Cat Society of New South Wales op-shop in Newtown was indeed uncanny as it, like Doris, needed protection and care.

There were two Early Kookas bands in Australia during the late 1970s and early 1980s - Anne Bickford's Sydney outfit and another, formed 6 months later, which played inner city pubs around Melbourne and featured the singer Leo de Castro. The Sydney band appeared to have begun gigging during the second half of 1979, judging by advertisements in student newspapers such as the University of New South Wales' Tharunka. and the University of Sydney's Honi Soit. They gigged in pubs around Sydney including the Civic Hotel, Sussex Hotel, the Southern Cross and the Rose Hotel. They feature in a 1979 poster promoting an anti-uranium dance at the Balmain Town Hall. The artist in that instance was Leonie Lane, who was also involved with Earthworks and the Wollongong-based Redback Graphix.

Acknowledgements

In the compilation of this article I would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of original artists Jan Mackay and Chips Mackinolty, along with Wendy Murray and Anne Bickford. Their activities in creating, preserving and promoting the poster are an important part of the story. Their input has added colour to the history of an already colourful piece of art and verified the thesis of Anne Bickford that each and every one of the Earthworks productions had an interested background - one perhaps more interesting than the work of art itself.

References

Bickford, Anne, Papers 1954-2002 (manuscript), State Library of New South Wales, ML MSS 9064. Available URL: http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110330065.

Brown, Pamela, Acme Demolitions - All We Leave is Memory, The Deletions [blog], 22 April 2006. Available URL: http://thedeletions.blogspot.com/2006/04/illustrated-lament.html.

Crawford, Marion and Zizys, Kate, Works of Protest, Proceedings of the International Multi-disciplinary Printmaking Conference, University of Dundee, Dundee, 28 August - 1 September 2013; Academia [website], n.d. Available URL: https://www.academia.edu/8367475/Crawford_Zizys_Works_of_Protest_wds. [Illustrated].

Edquist, Harriet and Vaughan, Laurence, The Design Collective: An Approach to Practice, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, 2012, 265p.

Gallo, Max, The Poster in History, W.W. Horton & Co., New York, 2000, 336p.

Gastin, Annie, Interview with Chips Mackinolty [audio], ABC Radio, Darwin, September 2010. Duration: 23.33 minutes. Available URL: https://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/09/10/3008427.htm.

Gosford, Bob, 'Pig Iron' Bob Menzies. From the other side of the cultural divide, Crikey INQ - Independent Inquiry Journalism, 25 September 2016. Available URL: https://blogs.crikey.com.au/northern/2016/09/25/pig-iron-bob-menzies-side-cultural-divide/.

-----, Queensland Police State, by Earthworks Poster Collective 1978, Crikey INQ - Independent Inquiry Journalism, 27 December 2017. Available URL: https://blogs.crikey.com.au/northern/2017/12/27/queensland-police-state-earthworks-poster-collective-1978/.

Grishin, Sasha, Not dead yet: Powerful prints with a social conscience, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 July 2014.

Kenyon, Therese, Under a hot tin roof: Art, passion and politics at the Tin Shed art workshop, Power Publications, Sydney, 1995, 152p.

Mackay, Jan and Mackinolty, Chips, The OO OO AH AH OO AH AH Dance, Earthworks Poster Collective, 1979, Sydney.

-----, Australian National Gallery, Canberra. Available URL: https://artsearch.nga.gov.au/detail.cfm?irn=85189. [Illustrated].

-----, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

-----, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Object 2007/56/72. Available URL: https://collection.maas.museum/object/365455. [Illustrated].

-----, State Library of New South Wales. Collection: Earthworks Poster Collective. Description: Promotion poster for an event held at the Tin Sheds Art Workshop, University of Sydney. The principal image is a reproduction of a photograph of a man in a dinner suit, holding a scroll. The suit has been over printed with green kookaburras. In the background are yellow and white flowers set against a pink fluorescent colour. The printer's mark is shown in lower left.

Mackinolty, Chips, After half a century of making posters ... Chips Mackinolty is a one trick pony!, Crikey INQ - Independent Inquiry Journalism, 15 January 2019. Available URL: https://blogs.crikey.com.au/northern/2019/01/15/after-half-a-century-of-making-posters-chips-mackinolty-is-a-one-trick-pony/.

Mayhew, Louise R., Girls at the Tin Sheds (Duplicated) [Exhibition],Verge Gallery, University of Sydney, 26 February - 21 March 2015.

McDonald, Ewen (ed.), The MCA Collection, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2012. Illustrated volume 1, page 102.

|

| Posters by Jan Mackay, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (McDonald 2012). |

Mackinolty, Chips, The Tin Sheds : Sydney, in Merewether, Charles and Stephen, Anne (editors), The Great Divide, Melbourne, 1977, 131-139.

Minton, Damien, Tin Shed Art Posters, 583 Elizabeth St Projects [Exhibition & Sale], 13-16 September 2018. Available URL: http://583elizabethstprojects.com/#/tinshedsartposters/. [Illustrated].

-----, Chips Mackinolty - 50 Not Out, 583 Elizabeth St Projects [Exhibition & Sale], 1September 2019. Available URL: http://583elizabethstprojects.com/#/chipsmackinolty/. [Illustrated]

Mosman, Petra, Girls at the Tin Sheds: Sydney Feminist Posters 1975-1990 [Review], Museum Worlds: Advances in Research, 2015 [webpage]. Available URL: https://museum-companion.berghahnjournals.com/2016/11/girls-at-the-tin-sheds-sydney-feminist-posters-1975-1990/. [Illustrated].

-----, Archives of the Australian Second Wave: History and Feminism after the Archival Turn, PhD thesis, Flinders University, 2018. Available URL: https://flex.flinders.edu.au/file/d16f6d1b-2386-4207-bc8e-6f8226628f1d/1/Thesis%20Mosmann%202018%20OA.pdf. [Illustrated - redacted].

Murray, Wendy [Mini Graff], Flickr [website], 2019. Available URL: https://www.flickr.com/photos/minigraff/. [Illustrated].

Music and Sound Effects - The Early Kookas [advertisements], Filmnews, Sydney, January - December 1980.

Organ, Michael, Yellow House poster 1972 [blog], 7 December 2015. Available URL: http://yellowhouseposter1972.blogspot.com.

-----, Toby Zoates: Posters, Painting and Performance [blog], 20 February 2019. Available URL: https://tobyzoatesart.blogspot.com/.

Ritchie, Therese and Mackinolty, Chips, Not Dead Yet: A Retrospective Exhibition, Charles Darwin University and Black Dog Graphics, Darwin, 2010, 72p. [Illustrated].

Silk Screen Printing at the Tin Sheds 1979 [video], YouTube, PB Productions, 2009. Available URL: https://youtu.be/Dzak1RaIkCU.

Wisniowski, Marie-Therese, Print Making in the 1970s and the New Millennium Art Essay [blog], Art Quill & Co., 22 December 2012. Available URL: http://artquill.blogspot.com/2012/12/printing-making-in-1970s-and-in-new.html. [Illustrated]

Yuill, Katie, Girls at the Tin Sheds: Sydney Feminist Posters 1975-1990 [Exhibition], University Art Museum, University of Sydney, 24 January - 24 April 2015.

Zagala, Anne, Redback Graphix, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2008, 128p.

---------------------

Protest Posters: | Alice's Tea and Yellowcake 1977 | Garage Graphics | Getting a head on the dole 1982 | Joe Gomez 1967-8 | International Women's Day 1920+ | Mary Callaghan 1975-89 | Ooh Aah Dance Poster 1979 | OZ magazine 1964-71 | Paris May 68 | Redback Graphix 1979-2002 | Steel City Pictures | Toby Zoates 1977-2024 | Yanni Stumbles 1980-86 | Witchworks, Wollongong 1980-84 | Wollongong in Posters I, II |

Last updated: 1 September 2019

Michael Organ, Australia

Comments

Post a Comment